Active Directory is the central system for identity and access in most organizations. That also makes it one of the first places an attacker focuses on after gaining initial access. Not because Active Directory is inherently insecure, but because credentials tend to be exposed in more places, and in more ways, than most organizations realize.

This first month of the Active Directory Hardening Roadmap is therefore fully dedicated to credential exposure and password hygiene. This is not a theoretical discussion. In nearly every environment we assess, weaknesses in this area significantly lower the effort required for an attacker to move forward.

Why password hygiene matters

Attacks against Active Directory rarely start with advanced exploitation techniques. In practice, they usually start with a valid account. That account does not need administrative privileges. A standard domain user is often sufficient to begin expanding access.

Once authentication is possible, an attacker typically stops guessing and starts discovering. The focus shifts to finding credentials that already exist somewhere in the environment. Active Directory attributes, file shares and locally stored credentials are common and reliable sources.

Strong password hygiene does not only reduce the likelihood of compromise. More importantly, it limits how far an attacker can go once initial access has been achieved.

How an attacker starts

Assume an attacker gains access to a single domain user account. The first actions are almost always reconnaissance.

At this stage, the attacker tries to answer a few key questions:

- Where can passwords be read rather than cracked

- Which credentials can be reused across systems

- Which accounts might provide elevated privileges

- Which accounts use weak or predictable passwords such as Winter2025!, Company2025!, Welcome2025!, or even the username itself

These questions quickly lead to a familiar set of locations inside the domain. LDAP-accessible directory data, shared file systems and credential stores on workstations and servers are usually the first stops.

The sections below explain how these sources are abused in real environments and how they can be addressed in a structured way.

Strengthening password policy and password management

Many Active Directory environments still rely on a password policy that was defined years ago. While these policies may still be technically valid, they often no longer align with today’s threat landscape.

Common findings include short passwords, accounts where the password matches the username, limited protection against password reuse, and service accounts that have not changed credentials for years. For an attacker, this means that a single captured password may remain useful for a long time.

A strong foundation starts with reviewing the domain password policy and introducing fine-grained password policies where appropriate. The focus should be on sufficient password length, preventing reuse, and enforcing clear lifecycle management for service accounts. This also includes explicitly blocking commonly used patterns such as SeasonYear, WelcomeYear, company names or username-based passwords.

Where possible, traditional service accounts should be replaced with managed service accounts to enable automatic and controlled password rotation.

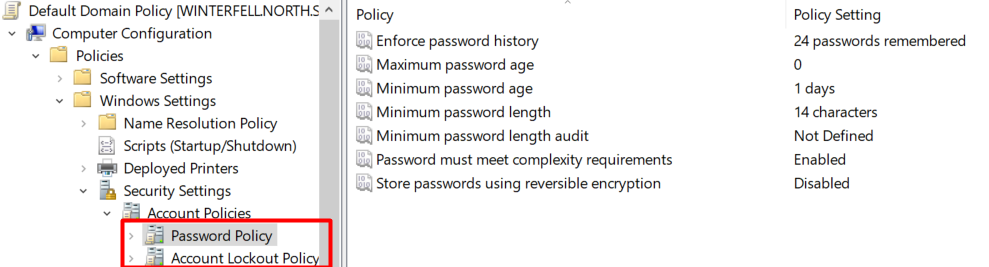

The screenshot below shows the location in Group Policy where the default password policy can be configured. Please note that this is the Default Domain Password Policy. There are also Fine-Grained Password Policies (FGPPs), which allow more specific settings per user or group.

Cleartext credentials in LDAP attributes

One persistent issue in many environments is the storage of credentials inside Active Directory attributes. This usually originates from legacy applications, scripts or operational shortcuts that were never revisited.

Attributes such as description, info or custom schema extensions sometimes contain usernames and passwords in clear text.

For an attacker, this represents one of the fastest ways to collect additional credentials. LDAP data in Active Directory is often readable by any authenticated user. This includes users, groups, computers and many of their attributes. Tools such as ldapdomaindump can extract this information at scale without elevated privileges.

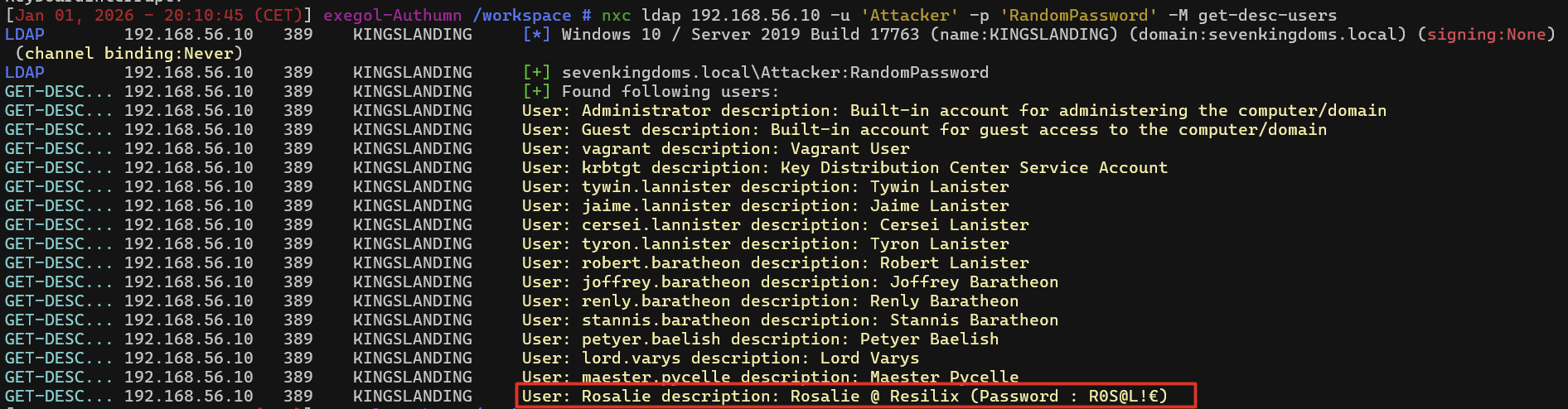

Proof of Concept

With a standard domain account, an attacker can perform LDAP queries and enumerate large parts of the directory. By searching for specific attributes or common patterns, cleartext credentials can sometimes be retrieved directly.

This is frequently observed in older applications, service integrations and temporary solutions that gradually became permanent.

What needs to be done

Perform a targeted audit of LDAP attributes across the domain to identify any stored credentials. Any findings should be systematically removed. Applications should be modified to use secure authentication mechanisms instead of static secrets stored in directory attributes.

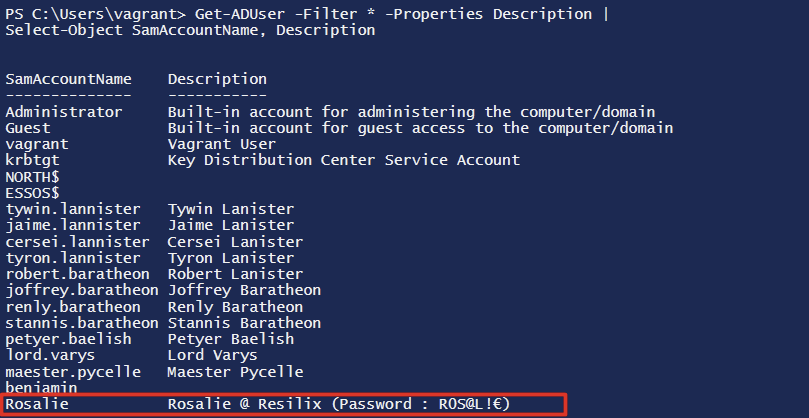

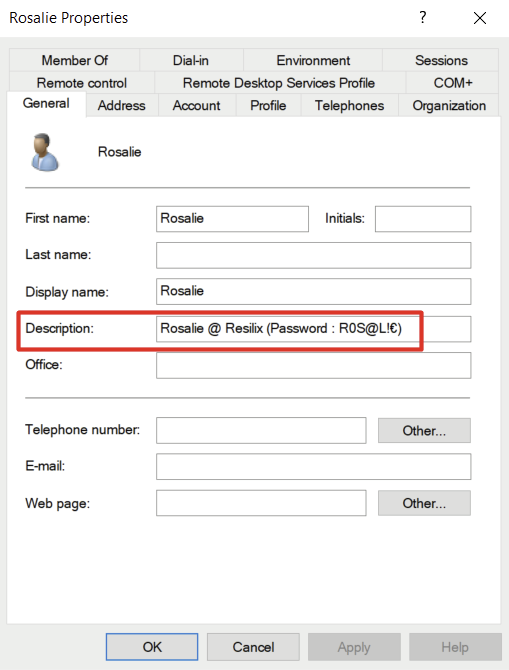

To support this process, a PowerShell script can be used to enumerate all user accounts together with the descriptions configured in their user settings.

The code block below shows the PowerShell script that can be used, and the screenshot underneath illustrates the results based on the previous server setup.

# Example PowerShell command to retrieve user description fields (via Get-ADUser)

Get-ADUser -Filter * -Properties Description |

Select-Object SamAccountName, Description

The final screenshot shows that the user description for the account rosalie contains the user’s password, which is set to R0S@L!€.

Cleartext credentials on file shares

File shares tend to grow quietly over time. New folders are added, scripts are copied around, documentation is dropped in temporarily and permissions are widened to avoid breaking things. Years later, those same shares are still there, often without anyone having a clear overview of who can access them or what they contain.

From a defensive perspective this creates operational risk. From an attacker’s perspective, it creates opportunity.

Attacker view

Once an attacker gains access to a regular domain user account, file shares are often one of the first places to look. No elevated privileges are required. In many environments, a standard user already has read access to a large number of SMB shares.

Manually browsing through folders is slow and rarely complete. Instead, attackers typically rely on automation to quickly identify interesting files across all accessible shares.

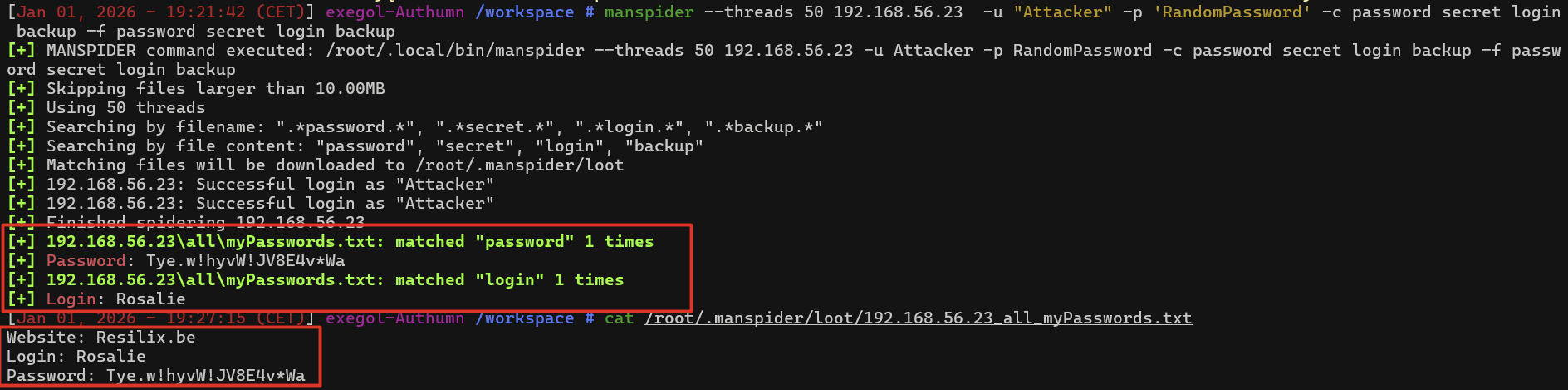

In the example below, we ( the attacker ) uses an automated tool to enumerate all SMB shares that can be accessed with the compromised account. Every readable share is scanned, and both filenames and file contents are searched for credential related terms such as password, secret, login or backup.

The output demonstrates that authentication succeeds using a normal domain user account. During the scan, a file containing sensitive information is identified and retrieved. The file contains credentials stored in clear text, including a website, a username and a corresponding password.

No vulnerabilities are exploited and no security controls are bypassed. The attacker is simply abusing existing permissions that were already in place.

In real environments, this technique frequently results in the discovery of sensitive information such as scripts with hardcoded service account credentials, configuration files containing passwords in clear text, old exports or backups with embedded secrets, and internal documentation listing usernames and passwords.

What makes this particularly effective is that the activity appears legitimate. From a monitoring perspective, the attacker is behaving like a normal user accessing shared files, making this type of abuse difficult to detect without strict access control and regular permission reviews.

Why this is so common

During assessments, the same underlying issues appear repeatedly.

Share permissions are often far too broad. Access is granted to large or nested groups, or temporary access that was never revoked. Over time, it becomes unclear who actually has access and why.

At the same time, ownership is missing. There is often no clear answer to who owns a share, whether it is still needed or what kind of data it currently contains. As a result, shares are rarely reviewed because no one wants to risk breaking something.

This combination leads to a loss of visibility. Organizations no longer know which shares exist, who can access them or what sensitive information they contain. For an attacker, that uncertainty works in their favor.

What needs to change

Reducing this risk starts with visibility. File shares need clear ownership, a defined purpose and a regular review cycle.

Access should be reduced to what is actually required, especially for shares containing scripts, configuration files or administrative material. Credentials should never be stored in files. Where automation is required, managed identities, secure vaults or other secret management solutions should be used.

This is not a one-time cleanup. Without continuous ownership and review, file shares will gradually drift back into the same state.

Credentials stored in browsers

Browsers are used by almost everyone in an organization, not only administrators. Employees use them to access work applications, but also to log in to private websites such as webmail, social media and personal services. Saving passwords in the browser is common and usually feels harmless.

The risk is not limited to administrative access. When browser credentials are stored on a system that later becomes compromised, the impact extends beyond the organization. Private accounts can be exposed, personal data can be accessed and, in many cases, passwords are reused across private and corporate services.

Password reuse remains widespread. Users often reuse their work password, or a close variation of it, on private websites. If those credentials are stored in the browser and later extracted, this can directly lead to compromise of corporate accounts.

Attacker view

Once an attacker gains local access to a workstation or server, stored browser credentials become an immediate target. This access may result from malware, phishing, lateral movement or abuse of legitimate credentials.

The attacker does not need to exploit a browser vulnerability. Modern browsers store credentials in predictable locations and rely on operating system mechanisms for encryption. If the attacker runs under the user’s context, extracting those credentials becomes trivial.

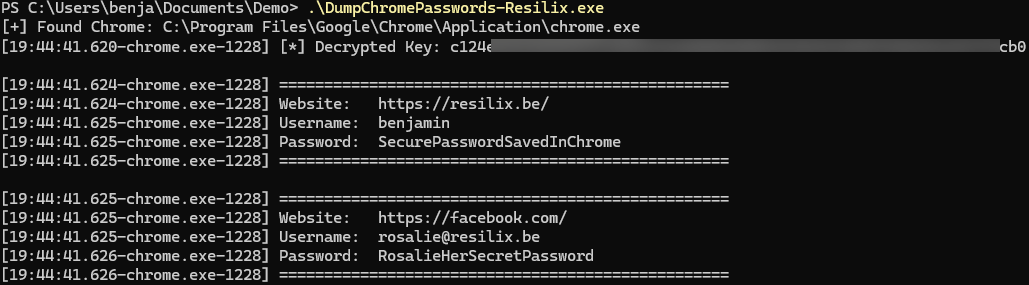

Readily available tools can dump stored passwords from browsers such as Firefox and Chrome directly from the command line. These tools read local browser databases and output usernames and passwords in clear text.

From an attacker’s perspective, this provides quick access to:

- Private email and personal accounts

- External services

- Internal web applications

- Corporate portals where passwords were reused

- Active Directory user credentials

The screenshot below illustrates how easy it can be to dump stored passwords using PowerShell. In this example, the tool dumpchromepasswords-resilix.exe is used to extract and display login credentials that are stored in Google Chrome.

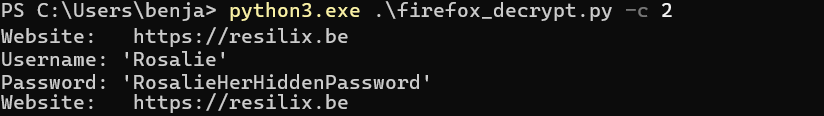

A frequently asked question is how secure another browser, or Firefox, is in comparison. These browsers are equally vulnerable and can have their credentials dumped if an attacker has control over the end user’s computer. As demonstrated in the screenshot below, Firefox passwords are dumped using the tool firefox_decrypt.py.

Why this keeps happening

Saving passwords in browsers starts as a convenience choice. Users log in frequently, systems are considered trusted and the risk feels abstract.

Over time, systems change. Workstations are reused, access paths multiply and the original assumptions no longer hold. What remains is a system containing valid credentials, often without the user realizing it.

Without clear policy and technical enforcement, browsers will continue to offer password storage, even on systems where it should never be allowed.

What needs to change

Organizations must make explicit decisions about where browser password storage is acceptable.

On servers and privileged systems, it should be disabled entirely using Group Policy. On user workstations, guidance and technical controls should be applied to corporate browsers and profiles.

Users should be encouraged, and where possible required, to use approved password managers that enforce unique passwords per service.

Wrapping Up

Credential exposure is rarely caused by a single mistake. It is usually the result of many small, well-intentioned decisions that accumulated over time. Together, they create an easy starting point for an attacker.

By addressing password hygiene and systematically identifying where credentials are exposed or reused, organizations significantly increase the resilience of Active Directory. Not by adding complexity, but by enforcing consistency and discipline.

This month establishes the foundation. The next steps in the roadmap build on this baseline with deeper and more advanced Active Directory hardening measures.

Let's Connect

Are you in need of assistance from our Active Directory Experts, or are you left with some questions after reading this blog post? Don't hesitate to fill out the contact form below!